We’re excited to announce the arrival of Lara Platman’s first article in a six-part series: Women in Motorsport. This time, Lara will be taking a look at the life of Hellé Nice, the remarkable Bugatti Queen.

TEST ADDITIONAL TEXT TO SEE IF IT DISAPPEARS.

Imagine the scene: Charles Rolls, Vincenzo Lancia and the brothers Marcel and Louis Renault rush past your eyes amongst the Paris Madrid Rally – then, fast in pursuit, comes Chamille Du Ghast, the first female racing driver. Hellé Delangle, carefully gripping the hand of her school teacher as she watched on the side of the road in the Beauce Region to the South West of Paris at the age of three. The year is 1903; could this be her first glimpse into what would become her lifelong ambition?

When I was asked to write about some of the fabulous historic women racing drivers that inspire me, I decided that Hellé Nice (her stage name) ought to be top of the list. You see, somehow I feel like I know this Bugatti Queen; how she would have drunk her coffee and eaten her baguettes at breakfast, and how she would have carried her lone leather suitcase from apartment to apartment after all her disillusioned relationships. I almost feel that I know her character, or that I had seen a film about her – but in fact, it’s all because I have read so much about this remarkable lady’s life.

Let’s begin with a Hellé Delangle, who danced at the Casino du Paris, where she earned her celebrity. With her earnings, she bought a little Citroen in 1920: the start of her motoring passion. In an automobile accessories shop owned by Henri Courcelles, a former WW1 pilot, she met Philip de Rothschild, and the three of them soon became the greatest of friends.

After Courcelles had entered the Le Mans 24 hours in a Lorraine-Dietrich, he and De Rothschild started to get Hellé into racing. In 1921, she went to Brooklands and sought to enter a race. But when her application was rejected because she was a woman, she was infuriated.

Her fury maintained throughout the 1920s. She raced when she could, but was never allowed to compete amongst the men.

Instead, she would go skiing to fulfil her passion for speed.

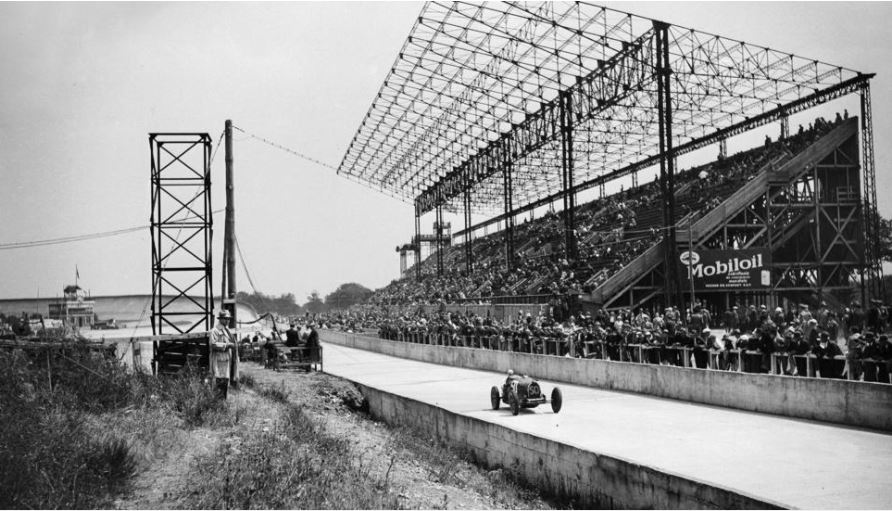

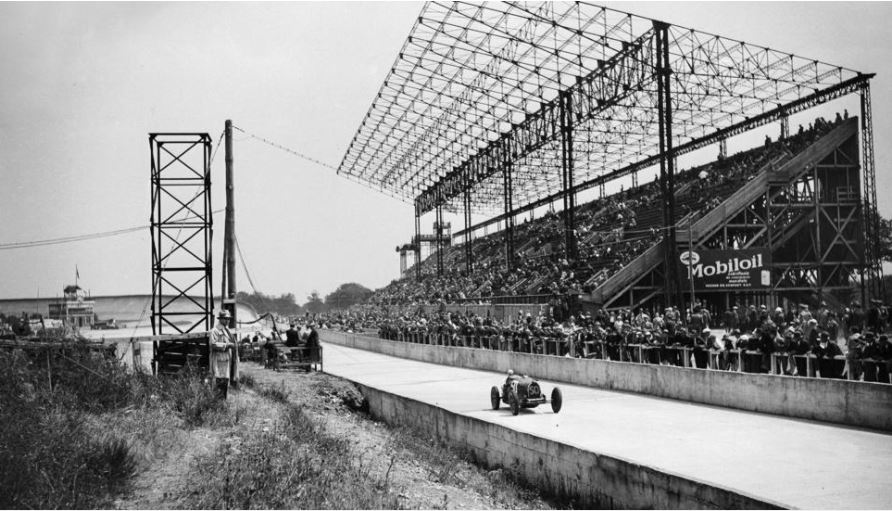

Being a showgirl, she jumped at the chance of publicity for Jules Daubecq and the Omega marque, and took part in the Women’s Grand Prix race at Montlhery – now in its third year in 1929.

She won it, passing the American Lucy Schell, Mrs Ferrand in her Amilcar and the Olympic athlete Violette Morris, in the Donnet.

Daubecq was correct in thinking that a glamourous woman would help shift stock – especially as his car had won the race.

“The driving was magnificent: nobody who saw it would feel able to argue that women drive less well than men,” wrote the newspaper L’Intransigeant.